Baffin Island - Couloirs, Polar Bears and Powder

A comprehensive report on the ski expedition of a lifetime.

Approaching the top of a classic ski descent. Photo by Vivian Bruchez.

Intro: Heroes, mentorship, and the foundations of an expedition.

Every young mountaineer has pondered the question, what will it take to bridge the gap between myself, and the people I look up to? We all have our heroes in this world. The people who do what we do, but to a level that almost feels unattainable to us. When I started to break into the ski mountaineering world, I began to look at the places people I looked up to have skied, and wonder if I’d ever get there.

The journey to the paradise of the north, really started with a trip south, when I met Chris Davenport in Portillo. After chatting with him and skiing a few laps at the summer ski destination, I learned about a trip he guided in Antarctica. Skiing in Antarctica? That sounded pretty unbeatable. In 2018, I found myself on a boat headed for the peninsula, in search of that childhood dream of skiing the planet. It was on that fateful trip to Antarctica where I met Brennan Lagasse. We were standing next to the railing of the Ocean Adventurer, looking out into the Beagle Channel.

Very quickly, I realized I was talking to an incredible human being. I was struck by how casually he mentioned skiing the Grand Teton and Himalayan first descents, he was somewhat of a superhero in my eyes. Despite his wealth of experience, he was never braggadocious, and talked about skiing the world in a way that made me believe I could do it too. More than just a skier, Brennan was a great person, someone who you could tell meant what he said, and cared deeply about the world and the people in it.

We skied together in Tahoe a bunch over the next few seasons, and quickly discovered that we aligned really well as ski partners. We shared philosophies on risk management, education and sustainability. I felt like not only did we have a good time skiing, but I always learned something new. In late 2021, Brennan proposed the idea of doing an international trip together. Somewhere neither of us had been, with a ton of steep skiing potential. Without giving it much thought I said “That’d be awesome, what do you have in mind?” When he returned the idea of Baffin Island it was like a jolt of excitement physically ran through me. “Woah” I thought. Baffin wasn’t just any ski destination in my mind, it was a real world manifestation of my ideal ski destination. An ultra remote collection of perfect couloirs, lined by granite big walls, that all spill out onto Arctic Sea Ice. The high walls hide the snow from the polar sun, preserving good snow. Not to mention the weather is typically quite stable, meaning you’re much less likely to spend your trip tent bound, as you might in Alaska or Patagonia.

I’d known about Baffin Island for a long time. First from the 50 Classic Ski Descents of North America, which featured the iconic Polar Star Couloir. Then from people I’d met in the ski world. Andrew McLean, who I also met in Antarctica, had pioneered much of the skiing out there. Jim Surette, another adventurer and guide who helped me in my early days of climbing, had been there as well. As I read through reports, it was pretty clear that the only people who seemed to go to Baffin were the pioneers and super athletes of the sport. Therefore, I never considered it a possibility for myself until Brennan brought it up. The answer was of course, hell yes.

Logistics, Mishaps & More:

As 2022 rolled around, we started to work out the logistics to get to Baffin Island. The Island’s proximity to populated regions of Canada gives the illusion that it’s easier to get to than other Arctic regions, especially living on the east coast. However, Baffin is among the hardest places on earth to get to. For starters, commercial flights to Clyde River are notoriously unreliable. On the slim chance your plane takes off, they might throw your bags off the plane to make room for supplies to remote communities. Your best option is a charter flight from Yellowknife. Secondly, once you’re on the ground in Clyde River, it’s still 60 miles to get to Kangiqtualuk Uqquqti (Sam Ford Fjord), home of the Polar Star. Initially, we intended to work with Weber Arctic, a heli ski service that operated out of Clyde. However, their communication with Brennan was spotty at best. They wanted us to stay in their luxury bungalow and sign up for their heli camp. We didn’t want a heliski camp, we wanted helicopter assistance, but to still have autonomy in our ski objectives. Eventually we seemed to work out a deal with them, including sending them our outdoor resumes to help them feel comfortable with our proposed trip. However, by the time we were both ready to pull the trigger, it was too late. We lost our slot.

Brennan and I went on a Sierra trip that spring for a consolation prize. We fought through isothermic snow, rocks, creek crossings, and the occasional boulder hole to ski Mount Bago. I developed a massive ear infection on day 2, but fought through and kept a smile on my face for our walk out. While the low snow and 50 lb packs made things challenging, we still had plenty fun. It further confirmed that Baffin was a trip we wanted to, were capable of, and should do together. However, as we began to revive the chain of communication with Weber, something unexpected happened.

Weber Arctic terminated their operation in Baffin, moving to Ellesmere Island instead to do year round skiing. In a world where streamlined operations seem to occupy every remote nook of the earth, we witnessed something I’ve never seen before. A highly coveted outdoor space just got way harder to get to. I couldn’t help but feel there was more to the story…

Regardless, now we had to do this the old fashioned way. The same way McLean did, and every other notable party since. With a 60 mile snowmobile ride, a rifle, and enough gear to open a shop. I couldn’t help being a little nervous, but I was equally excited. While a heli bump certainly eliminates some risk, I felt deep down inside it was the wrong way to do it. I wanted to earn those lines the same way my heroes did, taking everything that comes with an expedition of that nature. I felt like the mountains deserved that respect, and shouldn’t be cheapened for our personal desires. That being said, the idea of a sled breaking down in an Arctic whiteout, surrounded by hungry, lurking polar bears certainly kept me up for more than a few nights.

As we dove into the expedition mentality, Brennan suggested we bring Jeff Dostie as well, one of his most trusted partners. Realistically, going out there as a party of two would be very bold, and having a third increased our safety margin and our camp efficiency.

As 2023 rolled around, the trip of a lifetime suddenly got more epic, after Brennan skied a lap with Cody Townsend, who revealed he was also looking to ski in Baffin Island for The Fifty Project. After some discussion, his team, which included Bjarne Salén and Vivian Bruchez, decided to split the flight with our team. We would also camp together, and potentially ski together, but mostly ski as two parties of three.

I’ve always been a fan of Cody, but when he started attempting to ski the 50 Classic Ski Descents, I followed more closely. I’ve probably seen every episode of The Fifty, and even reached out on a whim to see if he wanted to ski Tuckerman Ravine with me for the project. It was a long shot given he had no clue who I was, and I doubt he ever saw it. Brennan actually knew him and was in a much better position to make the connection. As our trip approached, I kept very tight lipped about where I was going, and with whom. I’m already superstitious when it comes to talking about expeditions I haven’t been on yet, but with Cody on the trip it felt higher stakes. I really didn’t wanna be the annoying kid who spoiled the film. I didn’t even tell some of my closest partners we’d be on the trip together. Instead, I focused solely on preparation. Replacing old gear that might break on trip, skiing almost daily in the White Mountains, building my skillset, and avoiding my longboard at all costs for the sake of my ankles. I talked at least once a week with Jeff about gear. Suddenly my list was giving me more anxiety than the bears. Neoprene face mask? Overboots? Electric socks? How friggin cold was I gonna be on this trip?!? I pictured myself skiing in my high tech marshmallow suit, one drop of sweat away from frostbite. As time passed, my anxiety subsided and my flight date arrived, the only thing left to do was get there.

Getting there, and why we almost didn’t :

I started with a flight to Montreal, then to Vancouver. While waiting for a sandwich, I heard Brennan behind me. I was just starting to worry they were late. I met Jeff for the first time and we boarded the plane to Yellowknife. I was surprised to see so many empty seats. I sat down and enjoyed the fact we were on our last flight of the day. About half way through, in a weird pocket of cell service, I got a notification that one of my bags was delayed. I was screwed, our charter flight was the next day, could we even reschedule? I sank into a sea of stress, was I really about to be the kid that canceled The Fifty Project trip to Baffin? Our plane landed and I realized it was the ski bag that was missing, of course. On a half empty flight? They must’ve just thrown it off the plane.

I met the rest of the crew at the airport. They were missing ski bags as well, and hoping they would arrive that night. Somehow only half showed up.

We ventured over to the front desk to ask what to do. The guy there said very bluntly “Try to pester as many people in Air Canada as possible, if it gets to management that there’s a big issue with the bags, someone will take action.” It didn’t sound like a promising strategy, but it was the only limb we had to go on.

The next order of business was to contact Summit Air and see if we could move our flight. Cody was able to move it to Monday, but if the plane didn’t fly, the next opportunity was Thursday, half way through our trip. The next day we woke up and dedicated our whole day to managing the bag situation. We called every number, but found it impossible to connect with a human on the ground in Vancouver. Every call eventually got directed to a call center in India. Cody eventually got the idea to email the CEO of Air Canada, which despite jokes from the rest of the crew, actually got a reply. With the CEO on the case, we decided to go into town and handle other business. I bought a foam pad and a helmet in case my bag didn’t show. Jeff had enough extra gear that those were actually the only things I was missing. Overlander Sports in Yellowknife surprisingly had a lot of technical gear. The one thing they didn’t have was skis. We held back laughs as a teenager working in the store brought out a pair of Nordic skis, explaining how they were the perfect tool for what we were doing in Baffin. Vivian, who was also missing skis, even contemplated buying a snowboard for the trip.

Vivian considers the idea of skiing the Polar Star on xc skis.

Another looming task was to get Canadian money for Clyde River. The Inuits who would be providing our sled ride to the Fjord, didn’t exactly have a website for their services. It was all word of mouth among different crews of athletes. When we did get contact on the ground in Clyde River, we got different answers for price ranges on multiple occasions. Upon arrival in Yellowknife, we found out last minute there was nowhere to convert USD to Canadian. We spent the rest of the day draining various ATMs for as much as they would give us.

That night, as per recommendation of our friend from Overlander Sports, we ate at Bullocks, a crazy fish restaurant just outside of town. It was there when Cody got a call from a higher up in Air Canada, confirming our bags made it on the plane. Suddenly the vibe lifted substantially. We drove to the airport and waited for the singular daily flight to land. I belly slid across the table in excitement as I saw my ski bag unloaded from the plane. We were officially back on track.

Fly out day. Photo by Vivian Bruchez

The next morning, we gathered all our gear, and drove to summit air. With weather moving in, tensions were high about our potential for takeoff. We weighed the bags, weighed ourselves and ultimately discovered that we’d either need to lighten up 500 lbs, or hope for a clearing by noon so the small prop plane could land to refuel. Ultimately, we had no chance of either. Now looking at a potential trip ruining event, we pleaded for other options. To our surprise, there was a much larger jet, with longer flight capability, that was available the very next day, for an extra $1600 each. With the next opportunity to fly in the small plane being half way through our trip window, and commercial flights to Clyde having been grounded for 3 weeks straight, we decided to pay up. We spent the rest of the day at the climbing gym in Yellowknife, coincidentally with our flight crew. We walked out to a lake in town later on that had cliffs along its edge. Vivian led us on a shallow water solo we dubbed the “Muskrat Traverse”, due to the large muskrat swimming in the ugly water you’d certainly plunge into if you fell.

The opening crux on the Muskrat Traverse. Photo by Vivian Bruchez

The next day, lacking our rental car, we walked a mile from our hotel to summit air. We loaded in the mostly empty 64 passenger jet, and flew to Baffin at long last. On the ground we were met by Ben, who helped us shuttle our bags to the hotel. He introduced us to his son Andy, who was our Inuit guide for the trip. Him as well as two others, Jolly and Carlos, would sled us and our gear out to the ice the next morning. Andy would stay with us, providing us polar bear protection, and a ride to the base of each objective. Andy was younger than me by a few months, yet had the vibe of someone much older. He was concise with his words, self sufficient and organized. He appeared toughened by the harsh reality of living in the arctic, barely wearing gloves or a mask, while the rest of us bundled in full Denali gear. Brennan and Cody settled out a payment and we planned for departure late morning, the following day.

Happy to be in the Arctic. Photo by Vivian Bruchez

Day 1: Sledding In

We woke up early and got prepared for what could be a long, cold day. Beta we got from Emily Harrington suggested a possible 12 hour ride, that she was happy to have an 8000m suit for. We found out it can actually be as short as 3 hours, but was likely to be closer to 6 with the weight we had. I watched our local guides bundle our gear into rickety wooden boxes and tie them together with cord. As for us, we sat in a large box that shielded us from the wind.

Loading up the gear.

I came to find out that despite the appearance, the box was actually very secure, maybe a little too much so. As we sledded out of Clyde, we traveled through Arctic moraine lands, hitting bumps of sastrugi and occasional rocks. The wooden box didn’t budge, instead sending a shockwave through our bodies. It felt like I was being punched in the stomach repeatedly and wasn’t allowed to fight back for 3 hours. I wore my helmet to protect my head against the violent smack of the box.

Eventually we crossed a smaller fjord, and arrived at a large hill. I watched Cody attempt to climb it, then start sliding backwards. “Holy shit, what’s gonna happen to us?” I thought. Our local guides came up with a system to get the gear, and the crew up separately, using a new route around the hill. We also discovered that standing up in the box, or riding on the back of the Skidoos, was much better than sitting down. Throughout the day, I couldn’t help but notice there wasn’t very much snow anywhere. I couldn’t tell if it was wind stripped, or a low snow year. Either way, with the amount of logistics and money that went into this trip, I made peace with the fact that this was likely my one chance to ski here, and we might not ski anything. That was just part of the game.

We sledded out of a long gully and onto the frozen sea. Here, Andy quickly noticed a seal on the edge of its hole, and signaled for us to be quiet. He approached slowly, drew his gun, and killed it with a single shot. The seal instantly slumped into its ice hole, turning the water red with blood. Another group of Inuits commuting home on Skidoos circled up to see what was going on. They removed it from the hole, tied it to the back of the wooden structure, and moved on. I stopped to look at the seal, seeing a single drop of blood fall out of its nostril. I couldn’t help but have some empathy for this animal, but at the same time, I understood this was the way of life in the Arctic. This was how Andy’s people survived for thousands of years in this environment, first as nomadic people, now as a society in Clyde River. Hunting was always the source of life here, the only thing that changed was the tools. From harpoons to guns, and now with the added mobility of the Skidoos. Still, I wasn’t sure how to feel about the event I just saw. We got back to our journey, heading deeper into the fjord.

The seal, tied right in front of the dreaded box.

Soon, we noticed the granite walls growing larger, and couloirs beginning to reveal themselves. Our stoke grew higher as we began to recognize lines we’d researched. I felt excited as I saw not only was there plenty of snow in the couloirs, but they were even more epic in person. The scale of the fjord was hard to process. We pulled into a small cove beneath Polar Sun Spire, passing another party. They were two Nordic skiers who had already been on the ice for a few days.

We tried to get a spot across the cove from them, ultimately deciding it was too windy, and staging ourselves a few hundred yards behind them. What followed was a 3 hour long gear sorting extravaganza.

I spent at least an hour on the tent. The snow was so thin atop the pack ice, I had to make V-Threads for each of my stake out points. At the very least, I knew the tent wasn’t going to blow away. Cody’s team brought a massive cook tent, which retained heat incredibly well, and we all shared during our evenings in camp.

While making dinner, we started to ask Andy more about polar bears. As it turned out, we were wrong to think we were safer up in the fjord. We assumed the bears stay closer to sea and only come further up the pack ice if food is scarce. Andy informed us that they have dens in the mountains, and they walk out to sea in search of food. In other words, they travel right through where we would be sleeping for almost 2 weeks. When asked if he thought the polar bears might come here, he said between bites of dinner, “They might already be here.” We nodded quietly in understanding. Brushing off our bear anxiety, we changed layers, and got ready for our first day of skiing the next morning.

Day 2: Polar Star Couloir

We woke up around 10:00am to clouds clearing from the fjord. Suddenly, we could see the stunning rock features that shaped our surroundings. Our paradise was revealing itself for the first time. After eating breakfast and making sure everyone had water, we got our gear together and got ready for our first line of the trip. I felt tense with anticipation. This was by far the longest and hardest travel I’d done for a ski line, now it was finally coming together. Cody discussed us all skiing the Polar Star together, but giving them a head start, since we hadn’t been introduced into the story yet. We got all our gear in the sleds, and made our way slowly to the base. We drove past the Polar Sun Spire, admiring the 4000ft face Mark Synott’s team climbed in 1996, as well as Mount Beluga’s north face. As we neared the entrance, we could see the gash from a mile away. When it opened up, there was no doubt in my mind the Polar Star was among the greatest couloirs on earth. It was perfect. So consistent, with incredibly high, aesthetic walls. The pitch looked near vertical from where we stood, but as we approached on the Skidoos, it was as though it suddenly became 3D. The pitch appeared less steep, but the walls stayed the same. I don’t know how to explain it, but the closest I can come up with is that it’s like going into google street view in real life.

First time seeing the Polar Star. Photo by Vivian Bruchez

Cody, Bjarne and Vivian started up the first stretch. They quickly radioed back that they were assessing a touchy wind slab. As they climbed higher, it was clear only the first 200 feet or so were affected by the wind, and higher up was sheltered by the walls. After a while, they radioed back to us that we could start up behind them. We began to climb the couloir, marveling at the dark walls towering above us. The snow progressively got deeper, and the line got steeper, pushing into the high 40s. As we climbed the line, the occasional spindrift slowly descended the wall, sprinkling us with its magic. While the skier's right wall gets a little bit of sun, the line itself never gets light, keeping the snow perfect. It was odd to think we were standing in a place that never felt sun, in a region with 24 hours of daylight.

Booting up the Polar Star.

As we neared the top, I wondered if we’d get shut down by the last pitch. While Andrew McLean didn’t recall any ice in the top pitch, other parties have reported turning back due to blue ice hidden by a thin layer of soft snow. Then a call from Cody came over the radio saying they’d just topped out, and were waiting for us to catch up. Clearly whatever they found was passable.

Nearing the top, lost in the eternal shade of the Polar Star.

We came around the final bend, and encountered steep ice, coated with a thin layer of crusty snow, topped with fresh powder. It was just enough to get by. We took two tools out and pushed for the top. We emerged in perfect sunshine, with the right wall beginning to glow in the evening light.I was mesmerized by the landscape. Bjarne fired up the drone and Cody dropped in, we could hear the scraping of ice, then nothing for a while. Once the three of them got decently into the line, we got another radio call that we were good to move, and that the middle section was “really really really good”. We shuffled to the edge of the drop in, and Brennan started down the line, after a while I heard a whoop, indicating it was time for me to drop. So many years of looking at this line, and it was finally time to make turns.

Brennan, ready for action

I descended carefully into the icy section. With each turn, it took a second for the edges to bite. I skied very cautiously, moving edge to edge. Suddenly, there was a drastic surface change. Within 3 turns I went from ice skating, to almost getting sloughed out. I put the brakes on, switched to slough management mentality, and got ready for the ride of a lifetime. After some excellent steep turns, I saw Brennan in the safe zone and pulled in. Jeff came shortly after.

The next pitch was by far the greatest pitch of skiing I’ve ever done. Deep, blower powder, in a wide 40 degree couloir, for almost 3000 feet. I picked a section that didn’t look too far away for the next safe zone, but I was still adjusting to the scale of this line. My legs were toast from pitting steep and deep turns down the fall line, and I was barely halfway there. We took turns ripping down the line, spending each turn in disbelief, and pulling into safe zones out of breath. I hoped it would last forever, but our embrace of gravity did eventually bring us to the bottom. Upon emerging from the high walls a glowing sunset greeted us. While the sky never goes dusk, it does glow orange for a few hours, bringing new life to the fjord scenery.

Incredible line. Photo by Jeff Dostie.

I skied out to the pack ice and flopped over on my side, letting the moment wash over me. After so many false starts, such much time and energy devoted to getting there, we fucking nailed it. That in itself made everything worth it, and it was only the first run.

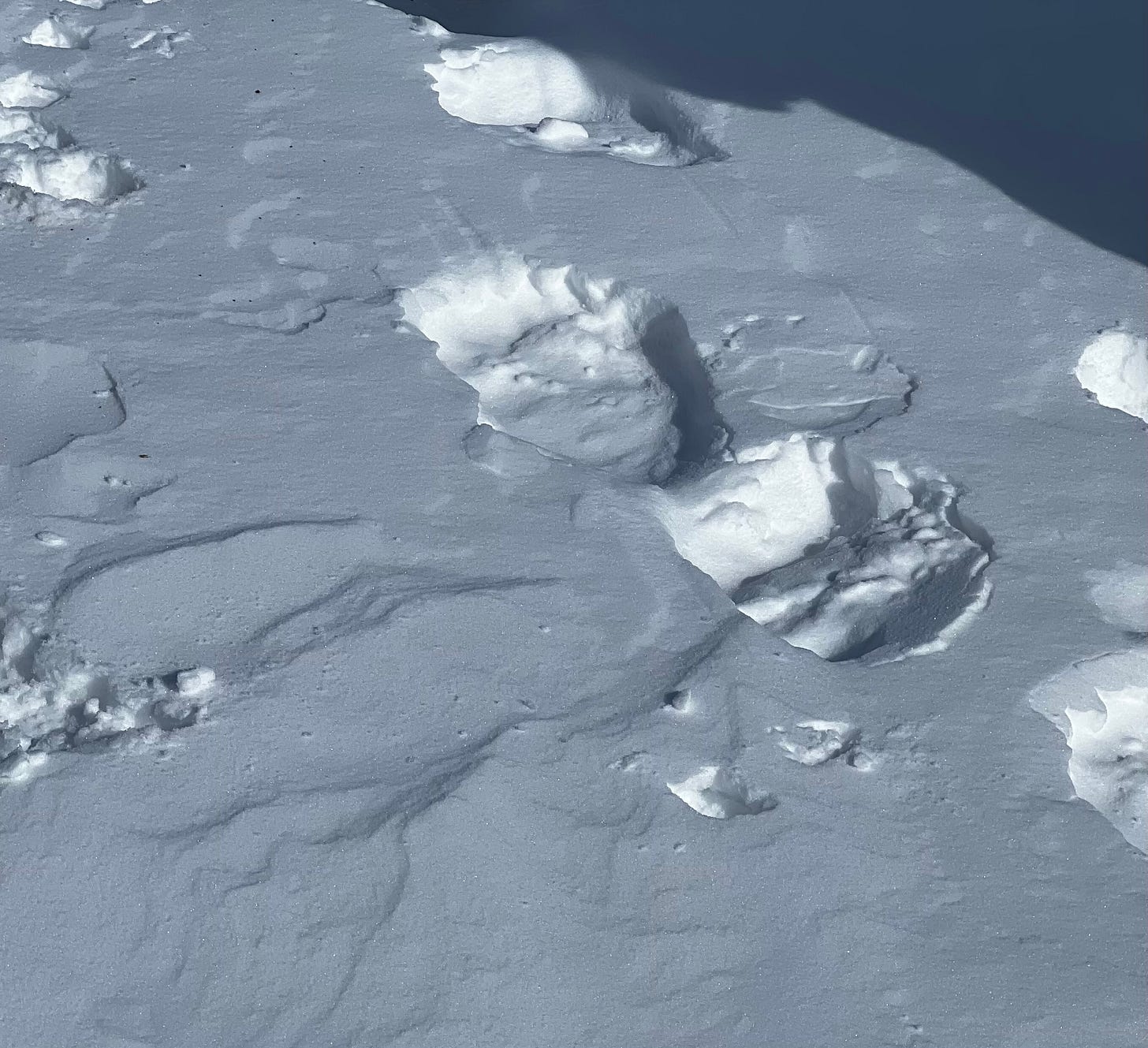

The perfect line, in perfect condition. Notice how it looks up close vs. far away.

Day 3: The AC Cobra

The magnificent wall at the heart of the fjord has come to be known as the Ford Wall. Skiers have since named all the couloirs in this zone after old models of Fords. The most notable of these is undoubtedly the AC Cobra. It’s as long as the Polar Star, and arguably as cool. While Brennan said his only specific objective on the trip was Polar Star and other than that he wanted to ski more obscure lines, I had a feeling we’d have a hard time driving past this line, and not wanting to ski it. Sure enough when Jeff and Brennan saw it for the first time, it took us about one minute to decide we wanted to try it.

A couloir I’d walk for a week to get to, thankfully, its only a 30 min ride from camp.

As we approached the Ford Wall, we saw Cody stop about 100 feet ahead of us. At first I thought gear fell out of the sled box, then I saw what he was seeing. Massive polar bear tracks. What was even worse, is that we could trace the line of tracks, starting from far back in the fjord, approaching our camp, then veering away. One of the deadliest predators on earth was walking right outside our cove, and we had no idea. I felt a wave of anxiety come back. That thing clearly saw our camp, and thankfully decided not to scope us out any further. Going through the process of managing objective hazard, I decided in my mind the best thing to do was to limit exposure. Which thankfully meant, spend as much time in the high mountains as possible, where the bears don’t go. We resumed our mission and I tried to convince myself there was nothing to be scared of. I felt better knowing Andy, who was with us all day, had hunted Polar Bears. Maybe that counted for mitigation? Either way, we continued with the plan. Cody’s team headed to ski a couloir near the Postage Stamp, and we headed for the AC Cobra.

Fear in it’s purest form.

I was very cold starting up the first pitch of the line in the wind, then as we reached the split and got shelter from the walls, we all quickly felt hot and started stripping layers. This started our trend for the trip, of Baffin Island being “The coldest, hottest place we’ve ever been”. You either needed all your layers, or wanted none of them, and all it took was a light breeze to change your mind.

Making our way up the AC Cobra.

Unlike the Polar Star, which meanders a lot, after the dog leg bend in the AC Cobra, you can see the top the whole time. It looked close enough that we convinced ourselves it was 1000 feet shorter than it actually was, then proceeded to spend the next 2 hours breaking trail. As we neared the top, we started sinking into thigh deep facets. Jeff was smart and broke out ascent plates. I convinced myself we were almost there, and proceeded to wallow way more than necessary. Brennan used it as another teachable moment.

Peaking over the edge.

We topped out to the lookers right of a large cornice, in a terrible, icy runnel. Certain we didn’t want to ski that, we walked over to the lookers left entrance and busted out the rope. Jeff slung a conveniently located boulder, and I went in on ski belay to jump on an isolated pocket of wind slab. I knocked it out on the first jump, then got another one to go with a ski cut. I yelled back up to them, confirming the snow wasn’t icy underneath, and unclipped from the belay.

About to test the wind slab on belay.

The first few turns were close to 50 degrees, and I moved slow to keep the slough below me. Once below the steepest stretch, I pulled into a safe zone. Jeff and Brennan skied right by me, milking the good snow for a long pitch. For the top 2000 feet we had excellent powder, even a few face shots. As we neared the bottom, the snow became grabby and eventually wind hammered, but we were more than satisfied with conditions. As we rode back to camp, we could see the sky changing. Weather was moving in, the question was, how bad would it be?

Day 4: The Storm

I went to bed that night thinking a lot about the bear tracks. I wondered if I’d get any warning that the bear was coming if it did approach our camp. As winds picked up, I hoped maybe our camp would be hidden by a whiteout, further hiding us from the bear. Eventually I fell asleep. Sometime around 3am I woke up and heard louder wind, and Brennan saying something about his backpack. With 4 hours of light sunset and 20 hours of full sun, I wondered if I’d slept in, or if it was still night time. I checked my phone and it read 3:01. “A.M. or P.M. ?” I checked. “Phew A.M.” I thought, and went back to bed without further investigating the voices outside my tent. Little did I know I caught a sound bite of Brennan responding to the worst windstorm ever, and I slept through the damn thing. I found out in the morning that the rest of the crew heard the cook tent buckle and spent the next hour using the Skidoos and a rad line to anchor it. Jeff and Brennan’s tent was positioned in a way that it blocked my tent from the brunt of the wind, likely why I slept through it. I felt guilty that I wasn’t there to help, but Brennan said they would’ve woken me up if they needed me. Still I made sure to pitch in as much as I could in fixing the dome tent. We put in a bunch of V-threads to replace the thinly T-trenched snow stakes, which relied on hopes and dreams to keep the tent from exploding. We fixed a snapped pole, and spent the rest of the day resting. While the wind in the cove subsided, we could still see it ripping on the fjord. We dried our gear and rested for the next day.

Day 5: The Model T

Whatever the conditions were before, they were different now. We needed to find a way to assess a line, in terrain where your only real ski potential is massive couloirs. Ultimately we decided to join forces as a team of 6, and ski top down on the Model T. That way we could snow cut any new slabs on belay, rather than booting directly into hangfire. Another team was booting up a smaller couloir just next to it called The Bronco. We drove past their line, scoping two smaller chutes that didn’t appear to go clean. We dawned skins for the first time on the trip, and skinned a valley to the left of the Ford Wall as our approach. The initial skin track was bare and rocky. At one point we even had to detour around a blue ice waterfall. Eventually we gained a long gully, which Cody set a smooth and consistent skin track up.

We roasted in the sun, reapplying sunscreen and adjusting our buffs, before ultimately reaching a massive chasm, with a huge snow funnel going into it. “Is that the top?” We wondered. Sure enough that was it. It looked steep, wind loaded, and the crux was obscured from view. We had a discussion to see if we could manage the line from both an avalanche and a technical perspective. Bjarne flew the drone into the chasm, and confirmed we likely didn’t need a rappel.

The massive entry funnel to The Model T, Cody is somewhere on the left ridge…

As we circumnavigated the funnel. We realized the entry was not nearly as steep as it looked head on, in fact, the right side was pretty low angle. Cody did a belayed ski cut, and confirmed the snow was soft and right side up, no shooting cracks. Still we kept to the low angle side, using terrain features to our advantage. Vivian and Bjarne followed him and radioed up that they were at the crux, and once they were through, they’d radio back to us. The next call was not one I ever expected to hear. “We’re sussing out a possible tunnel” they said. A tunnel? What the hell were we getting into? Minutes passed, we could hear excitement from within the line, even laughter. The next radio call confirmed we could move, and that this was one of the coolest things they’d ever skied. We crept into the line, admiring the impossibly steep wall of granite, that overhung like a wave at the top. Eventually we reached a chockstone. It had a completely flat platform on it, unlike anything I’ve seen in the middle of a line. I heard Cody say “come to the edge” we looked around to see who was going to do it. Jeff Side stepped to the edge and Cody explained the beta. The idea was the climb into this cave to the right. Plunge your ice axe, then lay on your back, and wedge your ski tails to ‘walk’ through this hole to the other side.

Brennan going to see what all this tunnel nonsense was about.

Brennan had his doubts, but he managed to get through with some coaching from Vivian. He was clearly stoked, but worried for me on the other side. As I climbed in, I laughed a bit, realizing that I never would’ve guessed in a million years, this is how we would make the Model T go clean. I found a way to sit down on the slope, wedge my ski tails, and inch one down, then the other. Once I got into the skinniest part, my tips were literally hitting the ceiling of the chockstone. I kicked my heels deeper and slid through. I uprighted myself on the other side. “What the fuck was that?” I said with a smile, admiring the feature. Rarely has skiing ever felt so creative to me, it made me feel the way rock climbing does.

The reward for managing the tunnel

What followed was some of the most beautiful skiing any of us had ever done. It was mellow in pitch, with little powder filled rollovers, sandwiched between two walls comparable to any Yosemite big wall. We skied out in the golden sun and gave each other high fives. The trip just kept getting better.

The Model T is just left of the largest rock wall.

Back in camp, the cook tent was becoming our community center. Every night we gathered around the stoves, traded stories over hot food, our wet gear becoming ornaments on the ceiling. The tent was usually 30 degrees warmer than outside, and our camp chairs let our bodies recover as we fueled up, and planned for the next day’s adventure.

Day 6: The Birthday Couloir

On May 7th it was my 22nd birthday. I was stoked to enter a new year of life on the ice, especially thinking how proud a younger me would’ve been to know this is how I’d spend it. All the guys wished me a happy birthday, and Jeff and Brennan agreed as a way to celebrate, we’d sled way past the Ford Wall, out to a couloir I wanted to check out. I saw it on the way in, it was wide, and appeared to curve to the right at a 90 degree bend, but the walls were so huge it completely obscured the line.

Is there more than meets the eye?

For all we knew it could be 300, or 3000 feet long. Andy didn’t mind the long sled out, and took us to the base of the line. At this point it felt like not only was the team working really well together, but Andy was really an integral part of it. As the trip went on, he began to open up more about his life, spend more time in the cook tent with us, and even try our wonky expedition food.

The ocean ‘schrund

We started up the couloir in the morning and quickly found that it did in fact, make a 90 degree turn. It was also way wider than we thought, and with a crazy double fall line.

Love when my ideas pan out!

As we topped out the line, we started to identify that each line seemed to have spatial variability, but throughout all the terrain, certain things were consistent. Bottom of the line was wind scoured and firm, middle was sheltered powder or chalk, very top was faceted. This line however, didn’t really top out. It sort of melted into an open bowl, revealing another, much skinnier chute above it. We ascended the low angle bowl, and climbed the steep chute, topping out to a ridge. The very top of the chute was wind scoured with heavy sastrugi, which made us wonder if it would be terrible survival skiing. We contemplated tagging the summit, but a mix of rocks and glare ice made us think the skiing likely stopped at the top of the chute.

Climbing up towards the final chute, the couloir is down in the obvious crack in the earth.

We enjoyed stunning views toward the mouth of the fjord. I felt like I fully processed where we were in the world with that view. We were looking out across the pack ice, realizing that Baffin Bay wasn’t far, and Greenland was the next stop. Eventually the biting cold motivated us to start descending. The chute wasn’t nearly as bad as it seemed, and the open bowl held shallow powder.

Farming Arctic powder.

The couloir looked insane from this perspective. It felt like all the snow in the area was just funneling us into a massive hole in the earth, and we were approaching the only path through it. The couloir itself skied more variable than I expected, with powder hidden on the upside of the double fall line. We skied out to the bottom, stoked this line panned out. While it likely wasn’t a first descent, given that I read trip reports detailing a similar line, I don’t think it has a name. We felt the Birthday Couloir best details the experience, but I also tossed out The Mothership, which I thought captured the ambiance of the line better.

Later that night, we realized it was taking a while for Cody’s team to get back. We later learned in camp they opened a new first descent on the Ford Wall that was incredibly complex, and they waited for the sun to get off it to avoid rockfall. They named their new line the Ford Fiesta.

Day 6: Split Echo

We woke up late and decided to do a day of scouting beyond the Polar Star. We sledded out to the Citadel Towers to scope the lines in that area. I had tossed around the idea of going for the second descent of the Polar Moon, a new line opened by Brette Harrington and Christina Lusti in 2022. However, having observed two seracs collapse on similar aspects, I had my doubts about it. Upon reaching the base, we saw a scary scene. Evidence of falling ice was littered throughout the base of the couloir. I started to think a lot differently about the line. It was beautiful, but it was Russian Roulette. The only way you survive that line is by getting lucky. I’ve had lines I’ve passed up on before because I didn’t feel safe doing them on a particular day, but I always opened myself to the potential to come back. This was the first line I ever wanted to do, that I realized I would never feel safe skiing it in my lifetime. It was an odd feeling. I quietly let go of my desire for it and we drove around the corner. We were hoping to find some hidden couloirs that no one had documented, but everything either looked too exposed, or too impassable. We turned around, passing the Polar Moon again, this time it had a fresh avalanche in it, triggered by icefall. It was as if the mountain was saying “good choice”.

The terrifying Polar Moon, see all the ice piled up at the bottom?

With it getting late in the day, we decided to ski what looked like a short line on the left side of the Citadel. It appeared to be about 300 feet long before terminating into thousand foot cliffs. With the shorter objective in mind, we thought it might be fun to have Andy walk up with us. Brennan gave him an ice axe and he walked up the first 100 feet with us before deciding to turn back when it got steep. He gave us a smile and said “That’s a good start” before descending. We were all in agreement that it was one of the coolest moments of the trip. Andy had confessed earlier that he felt that a lot of his interaction with outsiders had felt transactional, even hinting that Weber may have been pushed out of Clyde, because people were upset that they didn’t work with native guides. As outsiders coming to Baffin, we tried to make sure Andy felt like a part of the team, because in reality he was. Without him on the ice with us, our trip would’ve been substantially different. As we walked up the initial slope of the couloir, it felt like we were starting to gain his trust.

Andy climbing up with us.

As we continued up the couloir, we realized we’d once again underestimated the scale of Baffin Island. The line was actually about 1500 feet, and had a terrible sun crust at the top, where the line tilted to the east. It was clear we needed to stick to north and west aspects if we wanted good snow. Despite the bad snow, the line was still incredibly aesthetic. We skied slowly, admiring the walls and blue tide pools at the base. Jeff decided to name the line Split Echo, after two songs I’ve never heard before. I rolled with it.

Jeff in “Split Echo”

Day 7: The Mustang

We began the morning with a sled out to the Citadel one last time. Cody mentioned a line they looked at while we went further up the fjord, which was to the left of the Polar Moon, and had never been skied from the top. The bottom got skied by Hillary Nelson and Emily Harrington in 2022. It sounded like the top had a short mixed pitch, with a 30 foot slab guarding the upper couloir. We decided to scope it out. Upon arriving at the base, I realized immediately I misunderstood Cody. The 30 foot slab was the crux, not the full obstruction. There appeared to be a massive cliff that sealed off the bottom of the upper couloir. Possibly multiple rappels. Between the rock appearing chossy from below, and the facets we were finding above 3000 feet, we felt like going in from the top would be way too bold, because the anchor situation was likely to be desperate. A better mixed climber than me could probably do it from the bottom. Ultimately we decided it was too much to bite off, so we drove over to the Ford Wall to ski a deep couloir that splits left from the AC Cobra, known as the Mustang.

Ascending The Mustang, looks like another party scored it the day before.

We climbed the couloir quickly. And skied it in 3 very long pitches. As the sun touched the bottom of the line, I stopped and looked out to the pack ice. The bend of the fjord was glowing in the sun. I took a moment of gratitude before descending the last pitch. That night we began to work through our massive stash of cheese, salami and tortillas, by turning the cook tent into a quesadilla factory. I ate so many I didn’t even have room for dinner.

Day 8: Ford Explorer

Each day seemed to get progressively colder, but Day 8 was freezing. We originally planned on a long valley tour, but decided to stay in the shelter of couloirs due to low visibility and wind. Brennan had been eyeing an obscure line on the left side of the Ford Wall, that had a cliff guarding the bottom. We were waiting for it to feel right, and this felt like the day for it. We grabbed every ounce of technical gear we had on us, and walked up the short snow slope to the base. Of course in typical Baffin Island style, the cliff I thought was 5 feet was actually more like 20. The crux, an overhanging chockstone move, was only head high though. I tapped in a very suspect knife blade, and began attempting to pull the chockstone. I got a good hook and managed to tap my tool in like a piton, but everything above it was either low density powder snow or slabby rock. As I struggled for a hold, I decided to just mantel over the thing. I almost had my right foot on the key hold, when I felt myself barn dooring. I tried to step down, but my weight was too far back and I turtle shelled on my backpack and slid down to the belay ledge.

I was embarrassed and ashamed because I broke the number one rule of winter climbing, don’t fall. After collecting myself, I realized that I shouldn’t make a huge deal of it. I was barely 4 feet off the deck and I fell into powder snow without exposure. If anything, it was evidence I should try again because the fall was clean. This time, I tapped in a Lost Arrow instead, and left my backpack on the ground. I was able to find a higher stick, and mantel on my left foot instead. I moved nimbly through the easy ground above, and looked for an anchor. After about 20 minutes of searching through shitty rock and shallow snow, I managed to find a crack in some frozen choss that was ’good enough to belay from. It made me happy we didn’t go for the huge line on the Citadel. I hauled my pack, then gave Jeff and Brennan a Munter belay. As we walked up the powder hallway, we began to discuss how the M2-3 chockstone move was probably more evidence than not, that this could be a first descent.

Ascending the “Ford Explorer”

Especially with much easier, five star classics literally right next to it. It was hard to believe anyone would go here, and we found no evidence of a previous rap anchor. We climbed through a powder hallway, negotiated a skinny choke that reminded me of The Pinnacles at Big Sky, and topped out a spicy entrance. After just a few minutes at the top, we were all really cold. We started making our way to the first crux, a nasty rock band. Brennan and Jeff down-climbed it. I started to side step it, but ultimately decided it was too sketchy and popped my skis off as well.

Picking our way through

We skied through the pinnacle and into the powder hallway, which yielded great turns to the anchor. We rappelled over the chockstone one by one. Jeff and Brennan took their skis off, but I opted for the full value experience, keeping them on as I negotiated the rocky clusterfuck.

Jeff rapping the cliff band.

We opted to name the line The Explorer, to keep with the Ford theme, and also because you’d need to be an explorer to seek this line out.

Day 9: The Escort

With the last day of skiing on our hands, we wanted to keep it chill and just have a fun day, rather than push for anything crazy. It was a beautiful, sunny morning in camp, so Cody and Bjarne took time to finish up some film related stuff, such as getting portraits of everyone, and a group stoke shot. We also took the time to do something we’d been talking about the whole trip, get Andy on skis. Vivian, who in addition to being a world class ski alpinist, is also an amazing ski instructor, showed Andy the fundamentals of movement. With each step, he seemed to pick up on it so quickly. Eventually Vivian took him over to a small hill behind camp and had him sidestep up, and glide down it. Seeing the smile on his face as he skied down the tiny hill brought me a lot of joy. He was experiencing the purest thing in the sport, the simple love of moving downhill on skis. In a way, it’s that very feeling that shaped all our lives. The feeling that eventually led us to Baffin Island, without it, we all wouldn’t know each other.

After watching Andy ski for a bit, we decided it was finally time to get some turns in ourselves. We sledded further south into the fjord to see the last area we hadn’t scoped. We saw impressive big walls, but not many couloirs. We debated one beautiful, skinny couloir on the east aspect, but decided it was likely too icy. We turned around and headed towards Ford Wall. We looped through a small cove, where we saw a party of 7 skiers dawning their kites, but ultimately didn’t see any skiing that looked appealing. There was one line left on the Ford Wall we hadn’t skied yet, The Escort. We’d been putting it off because it didn’t look super inspiring, but upon reaching the base, it really gave us perspective on just how crazy this trip was. The Escort would’ve been a classic ski descent if it was anywhere in America. But we’d been skiing so many world class couloirs, we’d become snobs. The terrain on Baffin Island was just so incredible, it warped our perspective.

The Escort.

Stoked for another great run, we geared up and began booting the firm wind board. After so many days of boot packing in a row, we struggled to keep our boot liners dry, so we suffered from cold toes throughout the climb. Brennan even had to dig out a platform, take his boots off, and put in toe warmers. Despite dealing with some cold, we managed to top out the 2000 foot line in good time. We walked down the first 30 feet because it was wind blown down to scree, then dug out platforms to put skis on. The Escort is more exposed to the wind, so we needed to negotiate some sastrugi up high. As we got lower down, the run reminded me a lot of skiing on Mount Washington, with its wind buffed chalk skiing at a consistent pitch.

Classic Mount Washington conditions prepare you well for the Arctic.

Throughout the trip, I found myself thinking of the White Mountains and Big Sky a lot. Each had prepared me perfectly for skiing in Baffin. I stopped in the sun a little ways above the bottom, and made sure to take in the view. I hoped I would make it back there again someday, but with how much had to go perfectly to make it there, I had to make sure I got a good last look. We exchanged hugs at the bottom for a trip well done. That night, Carlos and Jolly showed up to stay the night in our camp, so we could pack up early in the morning.

Day 10: Sledding Out

We woke up at 6, ate a hasty breakfast and started to break down camp. I cut all the V-threads, packed my variety of warm gear into its respective stuff sacks, and put all the sharps into their protective cases for travel. We loaded up the sleds and looked around at our empty camp. The only evidence we were ever there was the footprints around our spaces, and the glassy ice that formed from our body heat against the base of the tents. While the sled ride into camp was cloudy and mysterious, the ride out was a bright and beautiful day. We rode past all the lines that we loved, and stared at the most eye catching peaks one last time. We felt alive as we sledded fast, reflecting on everything we accomplished.

Looking back at the fjord.

As we reached the mouth of the fjord, I felt like we were in a planet earth film as we looked at the endless frozen ocean. Andy told us he was going to stop at every seal we saw on the way out. We told him it was only fair since he stopped at every couloir for us. Most seals dove head first into their holes upon seeing us, we were able to catch a few by surprise. While our impromptu seal hunt on the way in was a bit of a shock to me, now that I better understood the way of life in the Arctic, I was rooting for Andy every time he drew his rifle. On the third try, he got one. Within 30 minutes they had it cut up and bagged. We were pointing out more seals on the way out, and Andy told us that unless he saw a really good one, he didn’t want to shoot another, because he already got one. To me this said a lot. Despite having the ability to, he didn’t want to take more than he needed. It was true sustainability in practice.

Andy on the hunt.

We moved back into the moraines and counted the miles until we were back in Clyde River. After the thousandth bump in the track, we finally saw the little hotel in which our expedition began. We unloaded the bags, and claimed our rooms. I exploded all my soaked gear throughout the room and set it out to dry, then took the most well earned shower of my life. We pooled our extra food and put it in a large duffel. We gave it all to Andy so he could have some for the next trip. Brennan gave him an unreleased FlyLow jacket, since he had a hole in his puffy all trip long. He was stoked to walk away with a stack of cash, a ton of food, and 6 skiers who were definitely going to recommend him as a guide to anyone planning a Baffin trip.

Clyde River.

With no restaurants in Clyde and minimal options at the grocery store, we cooked the last of our cheese into quesadillas and I rehydrated my last Mountain House meal. It truly felt like the expedition wouldn’t end until I reached my front yard. We managed to get the wifi to work for approximately 45 minutes, to connect with family and friends, and let everyone know we made it back safe. It was bittersweet to leave the ice behind, but I was looking forward to getting back into the world again.

Reflection:

While we were standing in camp during our pack up day, I remember Brennan saying how people at home were going to have trouble comprehending what we even did. We could tell them stories, and show pictures, but without standing there and feeling it, you just wouldn’t know. To be honest, I stood there, saw and felt it, and I’m still trying to process the experience. There’s just so many layers to it. At surface level, there’s the aspect of skiing a place I’ve always dreamt about. The sights we saw, and the couloirs we skied were truly unlike anything else in the world. It was really telling that a group of skiers 10-20 years older than me, who had all skied around the entire planet, thought this was one of the best places they skied. In a way I felt like everything in my life up to this point prepared me for this expedition, and I was happy I was able to hang in there with a crew that was so dialed.

The experience I gained on this trip was unlike any other. With everyone around me having been on countless ski expeditions, I felt like everyday I picked up new techniques to stay warm, dry and happy, in one of the harshest environments in the world. Furthermore, seeing how professional skiers, and veteran expedition skiers manage risk, was incredibly eye opening. All our discussions felt so deep and valuable, and I felt I learned more from what we decided not to ski, than what we skied. On lines this big, in a place this remote, there’s no margin for error. Everyday we discussed what hazards we could avoid, what we could mitigate, and what felt totally manageable. Even things as small as making sure we don’t overheat on the uphill, could greatly impact our safety out there.

Another big aspect of this trip was the team. There was a lot of experience within our team, but almost no ego. Everyone collaborated, did their part in camp, listened to each other's voices, and developed a team bond. Truth be told, I was intimidated to ski with this crew initially. Everyone in the crew was such a superhero in my eyes, how could I possibly share the load? By the time we got in our groove, it was like we were all just a bunch of buddies on a ski trip. It took a lot of pressure off my shoulders, and made me feel I belonged on the team.

Lastly, the cultural experience of working with the Inuit guides on this trip was so valuable. When we were planning this trip, my initial reaction to the idea of a heli bump was that it was a tarnish to the expedition experience. What I learned is that it’s so much deeper than that. When I think about it, it reminds me of something Cody said in the cook tent. The American idea of wilderness is false, because it suggests wilderness should be untrammeled by humans. However this land was originally inhabited by natives, who were a part of the ecosystem as much as any other living thing. In many of these lands, the only remnants of their culture is in the names of rivers and summits.

In Baffin, and many other parts of the Canadian Arctic, these regions are still home to native communities. They were here first, they live off the land we come to ski, and our travel to the region should benefit them, not some third party operation created by white people. During our time with Andy in the field, we connected with him, and learned about his way of life in the Arctic. We left with a new perspective. As more outsiders travel to Baffin each year, it is essential that things progress in a way that preserves the way of life for the people who depend on this land most. Hunting should always be permitted in the fjords, and athlete teams should hire local guides to access the terrain. My hope for the region, as the land is soon to become a national park, is that a system is created that benefits the Inuit people and athletes mutually, creates job opportunities for them, and preserves their hunting grounds. Since Baffin is one of the last places on earth that doesn’t have a straightforward way to travel there, we have a golden opportunity to get it right on the first try, and not repeat the destructive cycle of history that is present in so many other spaces.

Andy sharing our stoke for his backyard.